A water pipe made out of a … tree?

Quick! What are some of the types of pipes that have delivered water to Denver residents over the last 150 years?

We’ll start! Cast iron. Clay. Copper. PVC. Wood staves. Tree log.

Wait, did you say ... tree log? (Yes, we did!)

In December 2023, Denver construction crews working on a pedestrian safety and stormwater improvement project in northwest Denver uncovered part of an old water pipeline.

But this discovery was highly unusual. The workers, digging just south of the Federal Boulevard and West 25th Avenue intersection, had uncovered an old water pipe made from a hollowed-out tree.

Then a month later, in January 2024, crews discovered another section of a hollowed-out tree pipeline under West 25th Avenue between Federal Boulevard and Eliot Street.

“It really took us by surprise,” said Dallas Howell, construction project manager for the City and County of Denver. “The first section was badly deteriorated, but the second section was relatively intact.”

The tree pipes were installed in 1886 by the Beaver Brook Water Co., the private water supplier to the area that was then known as the town of Highland.

The tree pipe was 10 inches in diameter with an 8-inch hole bored through the middle for water to pass through. The pipe had wrought-iron bands wrapped around it for added durability. It was also coated in tar to protect the wood in the ground.

There was no record of the pipeline on the engineering surveys, so Howell said the construction team was very curious as to what they found.

“Finding a pipe like this is not something you come across every day, so it was definitely interesting to see such a unique piece of Denver history,” he said.

Work on the project temporarily stopped for an investigation.

“When these types of discoveries are made, we document the item to determine its historical significance,” said Barbara Stocklin-Steely, a senior historian with the Colorado Department of Transportation.

To do an analysis of the pipes, the city and CDOT worked with HDR Inc., the engineering company that did the planning and design work for the safety improvement project.

“We determined that what the workers found was a Wyckoff pipe,” said Megan Mueller, a cultural resource specialist at HDR Inc.

“The pipes were made by the Michigan Pipe Co. out of Bay City, Michigan. They were mostly used in the upper Midwest and Northeast during the late 1800s and early 1900s, so it was very surprising to see one west of the Mississippi.”

The most common types of water pipes in Denver at the time were wood stave, vitrified clay, brick and cast iron.

Mueller believes the Wyckoff pipe found by Denver’s construction crews is the only one of its kind ever installed in Colorado.

The man behind the tree-log pipes was Arcalous Wyckoff, who patented his “improved” pipe boring technique in 1855. The trees best suited for boring were Eastern and Northern white pines, which are commonly found in the upper Midwest and Northeast.

White pine trees grow to an average height of 80 feet and their versatile lumber has been used for everything from furniture to large masts for sailing ships.

The Wyckoff wood pipes were advertised as a cheap-but-durable and “more pure” way to move water. The pipes started being phased out around 1920 when other materials became the norm.

Denver’s early water days

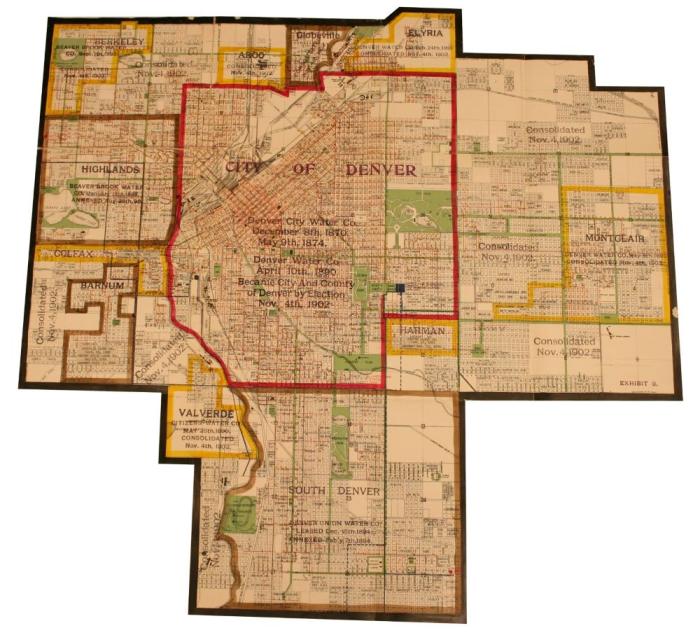

The discovery of the Wyckoff pipe offers a glimpse of what water delivery looked like around Denver in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The city’s population was growing, and there were about a dozen small water companies that got water from wells or the South Platte River.

Mueller suspects the companies were testing various types of delivery systems, which may have led Highland to try out the Wyckoff pipes.

The Beaver Brook Water Co. that installed the Wyckoff pipes obtained water from artesian wells in northwest Denver and stored it in elevated tanks.

The Beaver Brook Water Co. merged with the Denver City Water Co. in 1891. Five years later, in 1896, Denver annexed the town of Highland. On the water side, the Denver City Water Co. later became part of the Denver Union Water Co., which eventually became Denver Water in 1918.

What’s next?

After the discovery, HDR Inc., took samples of the tree pipe back to its lab for further investigation.

Mueller said they are looking for a place that could keep the artifacts for historical purposes, something that has been complicated due to the pipe’s old coating, which has special storage requirements.

As for the old pipe, some sections were removed to make way for a new storm sewer while the rest was left in the ground.

“I think discoveries like the Wyckoff pipe are important for the public to hear about,” Stocklin-Steely said. “The past gives us perspective about how far water delivery has come over the last hundred years and that the industry is constantly evolving.”

Denver Water would like to offer a special thanks to cultural resource specialists Megan and Andy Mueller of HDR Inc., and CDOT historian Barbara Stocklin-Steely for their extensive research on the Wyckoff pipe discovery and for sharing their report with Denver Water. Additional sources are waterworkshistory.us and Denver Water historian Holly Geist.