Where does your water come from?

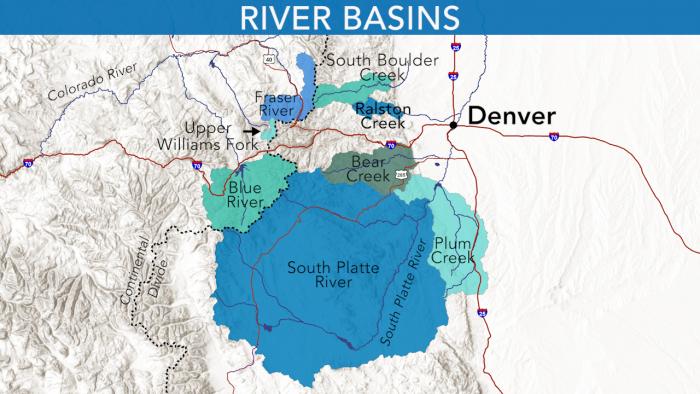

Denver Water, which provides water to 1.5 million people across the metro area, relies on a system that collects rain and snow from across 4,000 square miles of mountains and foothills west of Denver.

“Every year it’s helpful to have a large and diverse water collection system, because you never know how much snow we’ll see in Colorado and where it will fall,” said Nathan Elder, water supply manager at Denver Water.

On an average year, the utility captures 290,000 acre-feet of rain and snowmelt in its collection system. That’s roughly 94 billion gallons of water — or enough to fill up nearly 157 Empower Fields at Mile High.

The water flows down rivers and streams, then through a network of tunnels, pipelines and canals to treatment facilities in the Front Range to be cleaned for delivery to homes and businesses. Because most of the water comes from mountain snowmelt in the spring, water is stored in mountain reservoirs until it is needed.

Construction on the elaborate reservoir storage collection system began in the early 1900s when Cheesman Dam was built along the South Platte River southwest of Denver. Over the years, additional dams and tunnels were built to capture and store more water for Denver’s growing population.

Having a large and diverse collection system was critical to Denver’s growth because the city lies in a semi-arid climate.

Denver Water’s collection system is centered on the state’s mountains and foothills, because that’s where most of Colorado’s precipitation falls. About 80% of Colorado’s snow and rain falls west of the Continental Divide.

“The builders of the Denver Water collection system had to look to the mountains to ensure a reliable supply of water. There simply wasn’t enough moisture in the city to sustain the growing population,” Elder said.

Having a large geographic area to capture water is critical because it provides redundancy in times of drought, emergencies, infrastructure maintenance and improvement projects, according to Elder.

One example of the need for diverse sources of water occurred in 2020, when Denver Water had to close the Roberts Tunnel for maintenance.

Closing the tunnel meant no water could be brought to customers from Dillon Reservoir in Summit County. Dillon is the largest reservoir in Denver Water’s system. The Roberts Tunnel brings water from Dillon under the Continental Divide to the Front Range.

With water in Dillon Reservoir out of reach until the tunnel’s maintenance project was finished, Denver Water had to rely on water coming down the South Platte River and from streams in Grand County.

Another of Denver Water’s important water-carrying tunnels, the Moffat Tunnel, will be closed for maintenance in 2021, which means Denver Water won’t be able to access to water from Grand County during that project.

The Moffat Tunnel carries water, collected from 36 Grand County streams, and funnels it under the Continental Divide to be stored in Gross Reservoir before going to treatment plants in the metro area.

In times of drought, if the South Platte River Basin is experiencing dry conditions but collection areas on the West Slope are experiencing normal or above average precipitation, Denver Water is able to draw water from rivers and streams on the west side of the Continental Divide.

Wildfires are another big concern for the utility.

Eighty percent of Denver Water’s supply passes through Strontia Springs Reservoir, an area prone to wildfires like the 1996 Buffalo Creek and 2002 Hayman fires that impacted the reservoir and operations.

These factors are among the reasons Denver Water is planning to expand Gross Reservoir.

Denver Water’s storage capacity is imbalanced, with 90% of its storage capacity located in its South System and the remaining 10% located in its North System.

The increased storage in Gross Reservoir would allow more water to be stored in Denver Water’s North Collection system provide additional redundancy in the utility’s ability to have a reliable water supply for customers.

“Denver Water’s founders were not afraid to think big,” Elder said. “The foresight they had in the past greatly benefits Denver and the metro area now and will continue to help in the future.”

The following maps break down the collection system and service area.